Daniel Hernandez

Tim Dalton

FIQWS AR2

12/1/18

The Obscured Society of Wheelchair Users

Hello again! Thank you for taking the time out of your day to learn more about inclusive spaces, let us begin. This semester, my FIQWS class and I have been poking around the topic of our spaces: inclusive spaces, public spaces, and children’s spaces while also researching the significance of these spaces. To further understand the tentative topic of our built environment we touched upon works such as “McMansion Hell”, “Thermal Delight”, “Rooms in General”, “Light Up Gallaudet” and “The Land”.Understanding what makes up our built environment we then connected this with the lives we build around these spaces. The purpose of connecting all these works and have been to expand our view on the spaces we see nowadays. As a result, I have realized there are many places in our communities that are not inclusive to everyone. In a world full of people different from one another, why do we have spaces, architecture, and systems that do not meet the needs of everyone? It is upsetting to see in the 21st century there are not as many inclusive spaces as there should be, it is safe to say the United States is more diverse today than it was 100 years ago with people who require different needs. I believe one step towards meeting the needs of everyone is with the implementation of more inclusive space in our communities and equal prioritization of accessibility for able-bodied and non-able bodied people.

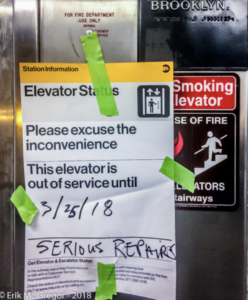

Exclusive design makes the life of people who need accommodation harder than it already is. Segregating design involves many little things that have large impacts on the life of a non-able bodied person, this includes: stairs, cracked sidewalks, door knobs, high shelves, manual doors, steep ramps, and the list goes on.To the right is a picture showing one of the many obstacles wheelchair riders must deal with that able-bodied people often overlook. Leonard Kriegel, author of “Beloved Enemy: A Cripple in a Crippled City”, gives his valid take on what it looks like to be a non-able bodied person living in NYC, he says, “The barrier it chooses to place before me are the barriers it chooses to place before all cripples trying to live as normal a life as the streets will allow.” (Kriegel). To clarify, Kriegel is expressing his view on how the barriers places upon him are placed on many other just like him, all trying to live their life as best as they can and because these barriers are everywhere, non-able bodied people cannot live a normal life. Sometimes these barriers are even put down despite the trouble it will cause. Kriegel shares a frustrating experience of getting nowhere when trying to point out the flawed curbs to the head of the city agency responsible for curb cuts, “Trying to show him what I was up against in my chair, I dutifully pointed out curb cuts with two- or three- inch lips and reminded him the city had mandated cuts of no higher than an eighth of an inch.” (Kriegel). Even when efforts are made to prove a point on how an unnoticeable curb height for able-bodied people is very troubling for non-able bodied people, nothing is given except for sympathy. These were two examples of how the exclusive design of our built environment makes the life even harder for non-able bodied people. Now let’s look at how the opposite, inclusive design, can make the life of everyone easier.

Inclusive design makes the life of anyone who requires different needs easier, having inclusive design does not negatively affect the rest of the community. I cannot think of one problem I have ever had with the inclusive design implemented in certain places, it is just something that is there that I can use if I ever need to. In contrast to the negative opinions Kriegel has about excluding spaces, here is a clear example of how having even just one inclusive space makes all the difference, Kriegel says, “… I loved it because my New York is a wheelchair city. And the aspect of walkways and plaza and atrium I loved most was how they offered me access, how open they were, how they led me into the city. Their accessibility was the gist of the identity that made the WTC so important a part of the city.” Kriegel shares his experiences of having the pleasure of once being able to freely roam around the WTC without the aid of anyone. This is such a precious vision of how it should be everywhere; enough accessibility and inclusive design for one who does not have the same privileges I do to roam and do as they please without the necessity of having someone there to aid them. The WTC that once shared the accessible identity of the city is now gone and we see even less of these accessible areas available. Here is another example of an inclusive space deviating from the accessibility of wheelchair users but also benefits a community and does not negatively impact others. Tobia Jacob a person that does not conform to a male or female identity gives his take on his experience with gender neutral restrooms, “The benefits of gender-neutral restrooms run deeper than simply providing safety for trans people. Gender-neutral restrooms have the potential to fundamentally transform the way we think about gender equality.” Not only does an inclusive space such as gender neutral bathrooms serve as a safe space anyone can use without being harassed, it also nurtures the potential of changing the way we think about gender equality. Besides the undeniable fact that inclusive spaces are good for those who need them, we can also see other sorts of good coming from these inclusive spaces.

In addition to inclusive spaces providing accessibility to those who need it, it can potentially nurturing relationships between people. Everyone wants to be included in something, in this case there are many barriers preventing wheelchair users from being

included. Jane Jacobs, author of “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” says, “Trust: trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many public sidewalk contacts.” What trust and relationship can a wheelchair user form on the public sidewalks when most of their time on the city sidewalks is spent maneuvering around high curbs, potholes, dog feces, and garbage. I would say a very negative attitude and a deprivation of social connection can be developed from having to deal with those obstacles day after day. David Brooks, author of “The Neighborhood Is the Unit of Change has” a great idea about how social infrastructure and having a place to gather and build a social connection is essential for people to survive in times of crisis. Brooks when comparing demographically similar communities says, “… fewer people died in South Lawndale in great part because there was more social connection there.” When times are tough the people you have strong bonds with are always the ones to back you up and keep you going. In NYC where segregation between the able-bodied and not-able bodied small designs that create major inconveniences prevent the development of these normal social interactions so necessary to have a normal life.

Places that exclude people that require accommodation bring about negative psychological effects. In many cases when one is isolated from the rest of the world and their right to move freely is restricted, it can bring upon not only frustration but serious psychological effects. What if every time you went outside or tried to live your life you were faced with immense frustration, it would drive me nuts. Luticha Doucette a New Yorker suffering with incomplete quadriplegia and requires a wheelchair to get around experiences first hand what it is to live a life in a community where segregation of disabled people is common place and accepted. She says, “Disability comes with its own unique challenges and trails, but the inability to engage with, and move freely through, our communities, or not being able to easily visit friends’ and relatives’ homes — and the social isolation that follows — because inclusive design is so uncommon, is a gross violation of our rights and is detrimental to our health.” (Doucette). Little did we all know that the very environment designed to make life easier for the majority of us is does so at the cost and health of the disabled. We see a similar perspective as Laticha with Sasha Blair-Goldensohn, a New Yorker unfortunately who now requires a wheelchair to move around. Sasha shares her frustration in her New York Times article, “New York has a Great Subway if You’re Not in a Wheelchair”, Sasha says, “I felt grateful to have come back so far, but each time a broken curb tipped over my wheelchair, a taxi refused to stop for me or a stalled subway elevator left me stranded, my frustration mounted.” Imagine recovering from head, lung, and spine injuries after having a tree fall on you, only to have things like a broken curb, stalled elevator and mean taxi drivers bring about even more disappointment and mounted frustration. Feeling this during many parts of the day cannot possibly be beneficial for one’s psychological health. Taking into account the views of many who experience first hand what it is to be not-able bodied in NYC, it is safe to say, NYC is an ableist environment.

NYC is an ableist environment that seconds the needs of disabled people. Sasha a working resident in NYC who relies on the MTA to get around is also faced with another problem, “New York’s subway is by far the least wheelchair-friendly public transit system of any major American city, with only 92 of the system’s 425 stations accessible.” This

means, Sasha either has to find a subway station that can provide her with an elevator to get onto and off the station or find other means of transportation. This does not only apply to Sasha or people in wheelchairs, all non-able bodied people go through the exact same thing. Of the 425 stations NYC has, only 92 provide accessibility, and almost all the time the elevator is out of order or stalls out on you.

The problem is not only the lack of sufficient accessible stations but the blatant apathetic attitude the MTA has for their riders that need accomodation. NYC MTA blatantly denies accessibility to their riders for the majority of their subway stations. If you are a NY resident who uses the MTA to get to their daily destinations, it is very clear to see there is little to no inclusive design in the stations that welcomes riders who are not-able bodied. What I might consider as the little inclusive design there is available in most stations are the handrails and occasional elevators that rarely work. Sasha as I mentioned earlier also has something to say about this, “On average, 25 elevators a day stop working, and these breakdowns are not quickly resolved; their median duration is nearly four hours.”

Imagine being on time with your commute to school or work and you find half the elevators available to you are broken down, now you have to wait 4 hours for someone to fix the issue or find an alternative way of reaching your destination, either way you’re late and this one conflict has messed up your whole day. What might leave non-able bodied people who are unable to access stations even more distraught is the time frame it might take to resolve this problem, “Though the agency is on track to retrofit 100 stations by the deadline, disability rights activists say that at this rate, the system will not reach 100 percent accessibility until roughly the year 2100.” (Nonko). If this is the case we might not see any changes soon and need to fight for faster results. On the bright side, our grandkids might possibly be able to enjoy the changes to our built environment for inclusivity that many so desperately need.

Without the exposure I had in class about our built environment and learning about the significance of certain spaces, I believe I would still be overlooking the importance of having inclusive spaces. There is more to the cracked sidewalks, stalled elevators, and high curbs that meet the eye. To many it means nothing but to the obscured society of wheelchair users, it means a world of frustration, pain, and struggle. It is clear much of the design in our built environment is outdated and there are elements that need to be taken into account from here on out. I hope this was informative and brought about awareness for the importance of having inclusive spaces and equal prioritization between able bodied and non-able bodied people.

Works Cited/Sources

Tobia, Jacob. “Why All Bathrooms Should Be Gender-Neutral.” Time.Com, Apr. 2017,ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=122517738&site=ehost-live

Jacob, Jane. “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” Vintage; Reissue Edition, (December 1, 1992)

Blaire Goldensohn, Sasha, “NYTIMES: NY has a great subway if you’re not in a wheelchair.” (March 29th, 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/29/opinion/new-york-has-a-great-subway-if-youre-not-in-a-wheelchair.html

Doucette, Laticha, “If You’re in a Wheelchair, Segregation lives.” The New York Times, (May 17th, 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/17/opinion/if-youre-in-a-wheelchair-segregation-lives.html

Nonko, Emily “The NYC subway has an accessibility problem — can it be fixed?” Curbed.Com, (September 21st, 2017) https://ny.curbed.com/2017/9/21/16315042/nyc-subway-wheelchair-accessible-ada

Brooks, David, “The Neighborhood Is the Unit of Change.” The New York Times, (October 18th, 2018)

Kriegel, Leonard, “Voices from the Edge.” Oxford University Press USA, 2004.

Photos not mine, taken from Flickr with permission.